|

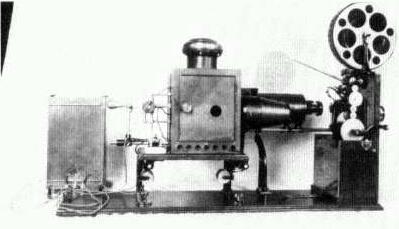

Edison’s Projecting Kinetoscope (circa 1901) |

Instead (as you can see from the 1901 ad below) the revenue model was based on selling the machines that played the films – i.e., Edison’s projecting kinetoscope.

One hundred and twelve years ago, the films themselves weren’t making anybody rich.

When the technology of motion pictures was new, the money was in the machines that played the content. Films were short, disposable and interchangeable. The movies were almost an afterthought for the businessmen like Edison.

No one had yet figured out the value of stars or emotionally-engaging stories.

In other words, one hundred and twelve years ago, films were like today’s YouTube videos.

Then, around 1913, a group of ambitious young outsiders (inspired by the money-making and storytelling possibilities of the new tools) established a revenue model for filmmaking that would grow into the Hollywood film industry we know today.

For almost 100 years, films with stars and stories were the basis of revenue in motion pictures.

That is, until the internet came along.

In the last six years the web and wirelessly-connected devices (like the iPhone and iPad) have disrupted the Old World of 20th century music and filmmaking.

Just as Edison’s inventions turned the 19th century on its head – Steve Jobs' inventions of the 21st century have knocked over the prior revenue models for music and film (below is an excerpt from the introduction of the first iPhone in 2007).

As in 1901, the revenue models for information and entertainment currently favor the companies that make the machines.

The companies that are building the best devices for accessing the internet and entertainment content (Apple, Samsung, etc.) and the companies making the best platforms for accessing information and entertainment (Google, Amazon, Netflix, etc.) are collecting unprecedented amounts of money.

Humans are clearly willing to pay for the things that improve our access to information, entertainment and stories.

But, right now, the creators of information, entertainment and stories are not getting a decent share of the revenue.

In some respects, 2013 is a lot like 1901. We are going through a phase where a huge percentage of the money is flowing to the companies that offer the best hardware.

In addition, certain companies, like Google, have profited immensely from building the software the enables data transmission and interactions.

Conversely, since the start of the 21st century, the value of many types of content has been undermined.

Much of the money that used to go to music and film creators has shifted to the companies that make the devices (e.g., Apple) and the software tools for accessing and sharing that content (e.g., Google, Apple’s iTunes store, etc.).

In the shift from the old paradigm (e.g., movie tickets, TV ads, selling physical copies, etc.) to a new paradigm (e.g., selling the devices that play digital content and the ad space and subscriptions that pay for access online), non-studio motion picture content creators have lost ground.

But, just like one hundred years ago, I suspect that the content creators are poised to make a significant come-back: Once digital devices are ubiquitous and a commodity and the paradigm-shattering convenience of these new devices is commonplace, the market will demand better and better content and we’ll figure out ways to charge users for that content and return a bigger share to the content creators.

Right now, there is no real market for non-studio films. But that is likely to change. And change quickly. As in the very earliest days of film, I suspect the revenue model(s) will rapidly evolve, providing huge opportunities for filmmakers and the studios that understand the online world.

Why am I so confident that there will be money for indie filmmakers in the near future?

The internet has changed a lot of things – but it hasn’t changed everything.

People still want to be informed and entertained.

Like film producer Ted Hope and scene-builders and online storytelling pioneers Brian Clark and Mike Monello, many of us from the Old World of indie films have dedicated ourselves to building out the infrastructure for the New World. (And note, these new opportunities are in addition to the revenue models that will survive from the Old World: As Steven Spielberg has recently observed, event films in theaters will continue to be a thing, even if you "have to pay $25 for the next 'Iron Man.'" Hollywood studios may be slimming down, but they aren’t going away.)

It used to upset me that so many many former film business colleagues (and almost all film teachers?) were stuck in the old ways, refusing to acknowledge the fundamental changes going on all around them. Now, I realize that (out of loyalty to an artform they love? stubbornness? an antiquated view of what constitutes culture? because Hollywood continues to have a grip on mass media?) many otherwise intelligent filmmakers will just never get it.

OK.

For the rest of us, who do get it, I think there is a responsibility to speak openly and honestly about the changes in the way that 21st century films will be made and monetized. If we don’t acknowledge what has happened, and start building a new revenue paradigm for non-studio films, a lot of filmmakers may continue to waste their time and money trying to make films for companies that (like Edison’s) will never value their work.

If you didn’t get it before, the unceremonious firing of Focus Feature’s James Schamus this week should have driven the point home.

Unfortunately, if you search online, you'll find much of the information that young filmmakers can access (e.g., the too-often-awful videos - like this one and this one - produced by Film Courage) teaching the now-mostly-pointless-for-indie-filmmakers Old World ways of writing, pitching, and distributing films.

Face it.

The Old World studios aren’t interested in giving indie filmmakers recognition or the opportunity to make real money as we push motion picture storytelling into the 21st century.

OK.

We don’t need them, any more than D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Sam Goldwyn, Adolf Zukor and L. B. Mayer needed Thomas Edison.

No comments:

Post a Comment