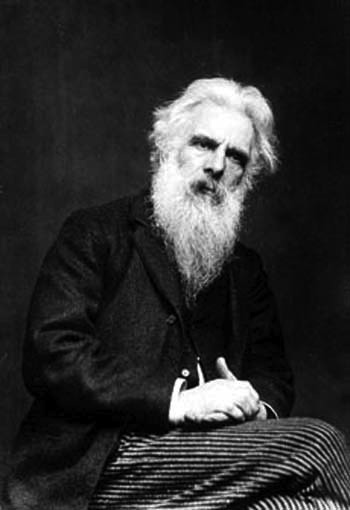

EADWEARD MUYBRIDGE

While Thomas Edison was busy establishing his lab in Menlo Park and Alexander Graham Bell was inventing the telephone after hours at Boston College, an eccentric British photographer named Edward Muggeridge (1830-1904) was finishing an epic journey through the American West and Central America. On that trip, Muggeridge traveling by himself, took photographs of native Americans (some of whom were still at war with the US) and killed a man in a fight over a woman in a California saloon.

In 1877, Muggeridge (who had changed his name to Eadweard Muybridge, note the novel oddball spelling of his first name) persuaded a rich San Francisco based railroad baron named Leland Stanford to underwrite a system for photographing motion; using twenty-four cameras, each triggered by the breaking of a trip-wire. For the first time, a rapid motion occurring in nature (a horse galloping) would be broken into component parts.

Muybridge’s accomplishment was not like Edison’s or Bell’s. In the strictest sense of the word, Muybridge was not an “inventor.” Muybridge wasn’t even a tinkerer. But in recording the images he photographed in 1877, Muybridge stands out as the first of a new breed of storytellers. Muybridge was the first photographer to capture the popular imagination with a “motion” picture. Although it would be another 15 years before strips of motion picture film would be commercially available, and another 3 years after that before films were projected to a paying audience, Muybridge was perhaps the first “filmmaker”, as the term is understood today.

What was revolutionary about Muybridge's idea was that he was the first to tell a story (even if that story only lasted for a few seconds) in a rapid sequence of photographs.

THE FIRST BATTLE OVER CREDIT: Muybridge had invented the technique and made the images of the horse. Stanford had financed Muybridge. Inaugurating a Hollywood tradition, Leland Stanford (acting as a producer) wanted to take all the credit. So Muybridge quit, left California and went East to work at a University.

LOUIS & AUGUSTE LUMIERE

In 1870, the Lumière family fled eastern France under the menace of the Prussian army and settled in Lyon.

Driven to succeed, the patriarch of the Lumiere family, Antoine (1840-1911), opened a photo studio in the center of town. He kept a close watch on the latest inventions. The tide of photographs taken by Muybridge’s apparatus in America fired Antoine Lumiere’s imagination: Moving pictures!

Antoine saw that his two boys, Louis (1864 -1948) and Auguste (1862-1954), attended La Martinière, the biggest technical high school in Lyon. With the proper technical training, the boys would take over the growing family business.

In 1892, British inventor William Kennedy Laurie Dickson (1860-1939), working under Edison, perfected the kinetograph and the kinetoscope, the first to record a moving image, the second to view it. But the kinetograph didn’t project the images. In Antoine Lumiere’s eyes, the Edison labs had failed.

The Lumieres were about business. Antoine saw the future of motion pictures AS A BUSINESS in distributing the images to a paying audience. In the autumn of 1894, Antoine Lumière asked his sons to work on the problem.

The combination of talents and expertise in the Lumiere household were unique. Within a matter of months, the brothers had come up with a plan. They would invent a machine to make and then project motion pictures to a room full of patrons. Within a year they had a working machine. They called their machine a Cinematographe. It effectively functioned as camera, projector and printer all in one.

The brothers immediately took their still secret invention into the streets – where they recorded numerous scenes of everyday life. The machine worked beautifully and the brothers couldn’t wait to project the results.

Auguste and Louis Lumière are credited with the world's first public film screening on December 28, 1895. The showing of approximately ten short films lasting only twenty minutes in total was held in the basement lounge of the Grand Cafe on the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris and would be the very first public demonstration of their Cinematographe.

While they had conquered the technical challenges, the Lumière Brothers were not born showmen. Their invention was thrilling, but their films – with the exception of a sequence where a train pulls into a station, that reportedly had audiences screaming and ducking for cover – and the first comic motion picture ever projected (see The Sprinkler Sprinkled from that Dec. 28th, 1895 program above) were boring. It’s as if, once they had perfected the machine, the Lumiere brothers stalled out. The Lumiere’s were the first, but not the last, producers without a story to tell. To their credit, the Lumiere’s quickly realized that there was little commercial value in a library of motion pictures that people could just as easily see by walking out into the street. They therefore decided that “motion pictures” was a field without a commercial future.

GEORGES MELIES

One of the most significant early innovators in manipulating time and motion for dramatic and wondrous effect was George-Jean Méliès (1861-1938).

A successful magician and owner of the Theatre Robert-Houdin in Paris, Méliès attended the first screening of the Lumière Cinematographe on December 28, 1895. In February of the following year, Méliès purchased a motion picture camera, and he began making his own films three months later. Cinema technology was just being developed, and Méliès studied the various new mechanisms. Méliès had projectors, printers, and processing equipment custom-made, based on other the inventions of other people or on improvements of his own design.

Méliès' first films were straightforward cityscapes and event films, patterned after the short films of the Lumieres, but soon he was using the camera to document magic acts and gags from the stage of the Theatre Robert-Houdin. By late 1896, Méliès was incorporating his knowledge of the mechanisms of motion pictures with the format of the stage magic skit, producing his first "trick" films. These short films relied on multiple exposures to create the illusion of people and objects appearing and disappearing at will, or changing from one form to another.

Over the next few years, Méliès was perhaps the most inventive filmmaker in the world. Not only did he experiment with what could be done inside the camera with special effects and multiple exposures, but also Méliès led in the development of a film language based on separate scenes edited together in chronological order. At a time when most filmmakers were content with single-shot films, Méliès was stringing shots together to make mini-epics like "Cinderella" (1899), which used seven minutes and 20 separate scenes to tell the popular fairy tale.

Méliès best known film, A Trip to the Moon (1902) was one of the longest and most elaborate of his trick film epics. The film was hugely successful, but not as profitable as it should have been.

By 1913 Méliès was deeply in debt. He was forced to sell off his studio and George Méliès disappeared from the motion picture business.

Georges Méliès was a forgotten man for years - until in the late 1920s Leon Druhot, editor of the influential Ciné-Journal, saw a familiar face selling toys from a small kiosk in a train station in Paris (see the photo above of Georges Méliès at work in the Gare Montparnasse). Druhot couldn't believe the fate that had befallen Méliès. Around the same time, a cache of Méliès films was discovered and painstakingly restored. With Druhot's support, in 1929 a gala was held to honor Méliès and in 1932 Georges Méliès received an apartment in a chateau converted into a home for aging cinema veterans. Georges Méliès died in 1938.

THE FIRST CASE OF MOTION PICTURE PIRACY?: A Trip to the Moon (1902) was perhaps the most heavily illegally copied film of its era, and while crowds around the world marveled at its tale of space travel, relatively little of this success translated into financial gain for its creator.

No comments:

Post a Comment